Updated: August 21, 2025

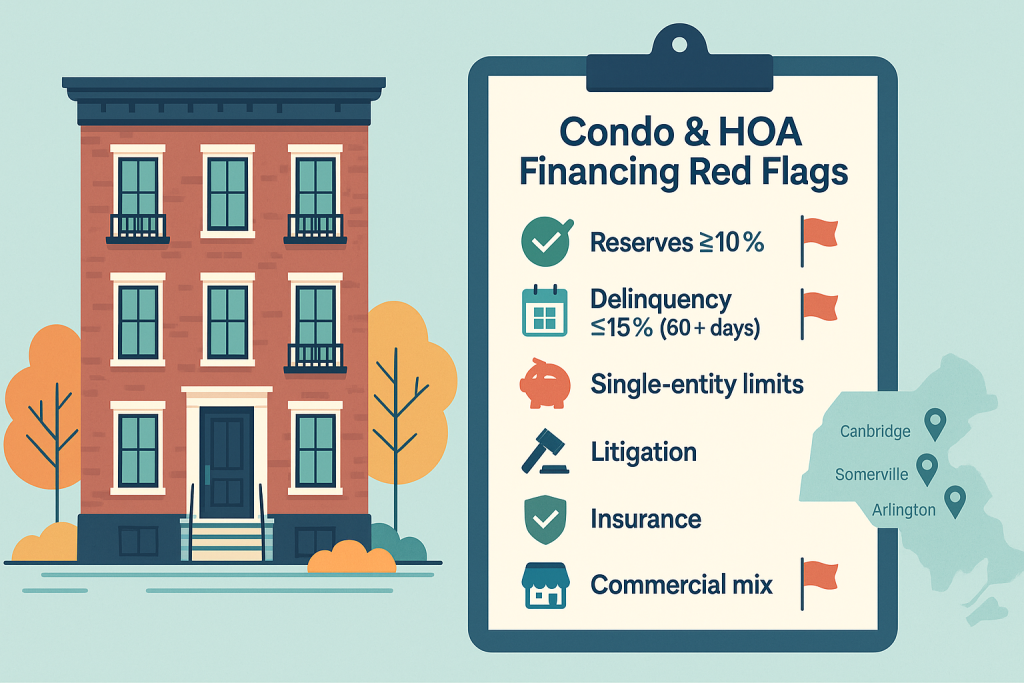

TL;DR: Conventional lenders want to see a clean budget with real reserves, low delinquency, reasonable owner concentration, manageable litigation, and solid insurance. If the HOA’s numbers are fuzzy—or more than a few owners are behind—financing can fall apart fast.

What lenders actually check (in plain English)

- Reserves in the budget: There should be a clearly labeled reserve line (roughly 10% of annual dues, or a current reserve study that supports a different amount). Special assessments don’t count as “reserves.”

- Delinquency: If about 15% of units are 60+ days behind on dues (regular or special), you’ve got a problem.

- Single-entity ownership: In 5–20 unit buildings, no one should own more than two units; in 21+ unit projects, no one should own over 20% of the units.

- Commercial mix: Too much commercial space in the building can spook underwriters (they see higher risk).

- Litigation & insurance: Minor disputes can pass; safety/structural issues are tough. Make sure master insurance is current and documented.

Why this trips up so many Greater Boston deals

A lot of older, well-run associations feel healthy but don’t present well on paper:

- “We save what’s left” budgeting. Money is set aside informally but not labeled as reserves. Underwriters look for a reserve line and a separate account.

- Quiet delinquency creep. A couple of owners slide 60–90 days behind and suddenly you’re over the threshold.

Quick story (names changed)

A 12-unit condo in the Greater Boston Area had balanced books, no formal reserve line, and two owners 90 days behind. The board had approved an $8,000 special assessment for roof work and figured that solved everything. It didn’t.

What we changed: We added a line-item reserve in the budget, opened a separate reserve account, set payment plans for the two owners, and documented the roof scope. The next buyer cleared condo review, and we closed with conventional financing.

Takeaway: It’s not about gaming the rules; it’s about presenting the building the way underwriters actually evaluate it.

If you’re a seller (or on the board), do this 30–60 days before listing

- Paperwork audit: Current budget, prior-year actuals, balance sheet (operating vs. reserve accounts), delinquency report by unit (show 60+ days), minutes, master insurance, any special assessments (terms + payoff options), and a short litigation letter if needed.

- Reserve proof: Add a real reserve line in the budget or have a current reserve study. Keep reserves in a separate account from operating.

- Delinquency plan: If you’re near the 15% threshold, start collections or payment plans now—don’t wait for the buyer’s lender to discover it.

- Ownership concentration check: In small buildings, confirm no one owns >2 units; in larger projects, confirm no one is over 20%. Related entities/spouses can be combined, so look closely.

- Commercial exposure: If there’s ground-floor retail, estimate the share. If it’s high, set expectations early and loop in a lender who’s done these locally.

If you’re a buyer (or representing one), pre-flight the HOA before you fall in love

- Ask for an underwriter-ready packet with the items above.

- If the project is borderline, choose the right review path (limited vs. full) and a lender who knows Cambridge/Somerville/Arlington/Greater Boston condos. Sometimes the loan-to-value you pick controls which path is available.

Red flags you can spot in five minutes

- Budget shows “surplus” but no line labeled reserves

- One bank account for everything

- Multiple owners more than 60 days behind

- “We’ll just do a special assessment if something breaks”

- No documentation for current litigation (“our attorney is handling it” with no details)

If you see any of these, we can usually solve it—just plan for extra documentation or a different loan structure.

Local context: what’s normal here

- Many 2–12 unit associations in Cambridge and Somerville were converted from older multi-families. Great character, but budgets and record-keeping can be casual.

- Arlington has a mix of small associations and larger, professionally managed buildings. The larger ones usually pass review faster because the paperwork is tighter.

- Older roofs, brick exteriors, and porches are common—none of that is a deal-killer if reserves are real and delinquencies are low.

What to do next

- Sellers/Boards: Send me your budget, balance sheet, and delinquency report. I’ll flag what a reviewer will flag and give you a concrete punch list.

- Buyers/Agents: Before you write the offer, I’ll do a quick “project review preview” so you don’t lose time on a building that won’t pass.